Steffan Nero: The record-breaking Australian blind cricketer who has found a ‘family’ in the sport

CNN

—

Growing up visually impaired, school wasn’t easy for Australian Steffan Nero. He remembers struggling with anxiety and being “very quiet,” “lonely” and “probably weird as well.”

His life changed when he discovered visually impaired sports – notably cricket.

“I was actually a different person when I was with other vision impaired people. I was actually a very outgoing kind of person, very energetic,” Nero told CNN Sport.

“You’re part of a group. You’ve all dealt with the same experiences. You all can speak to each other, obviously, especially when you have the older players as well … They’ve got lessons that they can (teach you about) obviously how to go about things as well.

“It’s all a big family. You’re all trying to help each other out, to push each other as well, but also support each other as well. You have a brotherhood … build bonds with your mates that will last for forever.”

That brotherhood helped Nero establish himself as an international athlete in multiple sports and in June, he etched his name into sporting history when he scored a record-breaking amount of runs in blind cricket.

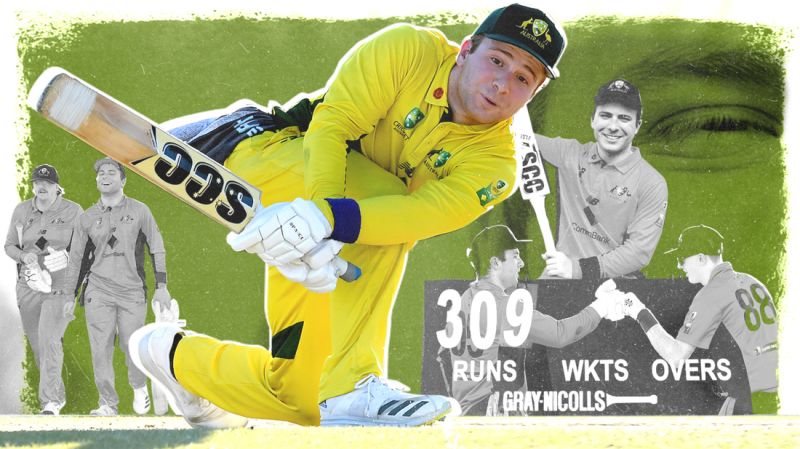

Nero scored 309 runs not out against New Zealand, smashing the previous record of 262 which had been set at the 1998 Blind Cricket World Cup by Pakistan’s Masood Jan.

His record-breaking effort saw him feature in domestic and international news outlets – which is when the achievement started to sink in for Nero.

“I always say: ‘Just take that first step.’ It probably will be the hardest thing you ever do. But once it happens and you’re involved in that kind of group … in that community, I think things get much easier and can be quite a really rewarding experience.

“Particularly in Australia, so there’s so many sports available now. There’s goalball, there’s tennis, there’s soccer, there’s cricket, AFL, golf.

Nero was born with two sight impairments.

He has a rare inherited condition called Achromatopsia which causes sensitivity to bright light and loss of color vision. According to the UK’s National Health Service, it affects roughly about one in 30,000 to 40,000 people.

Nero was also born with congenital nystagmus, which is an involuntary movement of the eye, meaning he struggles to “focus on anything [and] everything is very blurry.”

Due to those conditions, playing sport at certain times of the day – with specific light conditions, such as when the sun is low – can be particularly difficult for Nero as his eyes struggle to focus.

Nero remembers being introduced to sport when he played cricket with his dad at the park. Eventually though, they had to stop as he couldn’t see the ball well enough.

He tried his hand at other sports instead; he practiced karate for a few years, he played goalball – a Paralympic sport – as well as football, representing Australia in many of them.

But it wasn’t until two of his friends suggested that he come try his hand at blind cricket that he really found the sport for him.

Playing cricket was purely about enjoyment at the beginning for Nero, though adjusting to a completely new sport is tough.

Blind cricket differs from the able bodied version in a number of ways. Teams are made up of players of varying visual impairments, the ball is made of hard plastic with ball-bearings inside to allow players to hear the ball and bowlers bowl under-arm rather than over-arm.

Nero remembers one training session where one of the more established players, Lindsay Heaven, took him under his wing.

“He taught me a lot about the different shots to play and also taught me a lot about life as well,” Nero explained.

“And he said: ‘If you really push hard at this, you can go well in the sport.’ And that kind of encouragement and support pushed me to train a bit more and more.”

It wasn’t smooth sailing though. Nero missed out on being selected for the 2015-16 Ashes series against England; something he says he used as motivation going forward.

That motivation helped Nero become a regular Australia international.

In 2017, he benefited from the tutelage of Pakistan’s coaches who were flown to Australia to coach batting technique as he attempted to “replicate players from the top two countries in the world (India and Pakistan),” according to Cricket Australia.

And in June, all that training paid off in his record-breaking afternoon.

Nero says in the match against New Zealand, he was just starting “as any opener obviously would, just trying to get their team in a strong position.” It wasn’t until he reached the 200-mark that he realized he might be onto something special.

Having reached 309 not out – surpassing the previous Australian record of 222 held by Eugene Negruk – Nero remembers the fatigue he felt afterwards.

“I was just kind of walking off and I was like: ‘Oh my goodness.’ I didn’t realize because I was in the zone,” he said.

“What people don’t realize about vision impairment is … you actually use a lot more energy trying to concentrate on things. Typically a lot of people have a lot of headaches and stuff as well and get quite tired after straining your eyes for that long.”

Receiving coverage from some of the world’s mainstream media was a particular highlight of Nero’s because of the potential beneficial impact it could have on other disabled athletes and also changing people’s perspectives on the abilities of disabled athletes.

“The majority of people were very impressed or saying: ‘Oh, wow, I didn’t realize there’s this game and disabilities sport as well,’” he said.

“I think it helped to kind of change people’s minds a bit about what disability means as well because sometimes when you mentioned blindness or vision impaired, people usually assume the worst, which means obviously someone who’s very like closed off, shuffling around, very quiet. Whereas, obviously, it’s not the case.”

Nero added: “And because people see in the mainstream media as well and they might have a friend who has a disability or their son, daughter; people see it and they go: ‘OK, that’s what’s available out there as well.’”

Although the majority of the feedback he received was positive, Nero admitted there was a small minority who took to social media with negative comments. He saw some making jokes about the nature of disability cricket, while some attempted to devalue the achievement, saying: “Oh, it’s just disability cricket.”

But Nero made sure to never let those few dissenters get him down. “That’s the way it is on social media. Everyone kind of deals with that even if you don’t have a disability. So for me, I just after a while stopped looking at the comments and stuff as well and just kind of ignored it and said: ‘You know what? This is something that I think is really positive for blind cricket, for people with disabilities in Australia as well.’”

Nero’s aspirations for his own personal game are sky-high, even after his record-breaking run score. But his ambitions for how much he can help the next generation of disability cricketers is astronomic.

“I want to try and give back to the game as well and support the younger players coming through because, obviously, they’re the future of the game. Because I know how much it helped me when I was growing up.”